SULGRAVE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT

WARTIME MEMORIES OF THOSE WHO LIVED IN SULGRAVE

DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1939 TO 1945.

This is the first in a series of articles based on the stories of the people of Sulgrave as recounted during the Oral History Project, 2003 - 2006, supplemented with other appropriate material. It deals with general impressions of life in the village during the war years. More specific articles dealing with Evacuees and the Prisoner-of-War camp will appear later. Comments on these stories will be welcomed, together with any further relevant memories and photographs, which will be published on this website under the general heading of "Sulgrave Oral History Forum".

(Note: Transcripts taken from the original recordings are in italics. Other text is by way of editorial explanation).

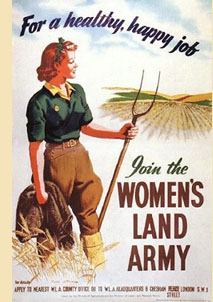

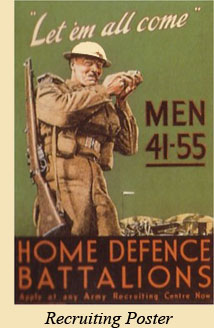

The village was, of course, a very different place during those years. Everyone had to contribute to the war effort. Men who were not required in important “reserved occupations” such as agriculture or aluminium production in Banbury were away in the armed forces. Women were required to “do their bit”, taking the place of the men on

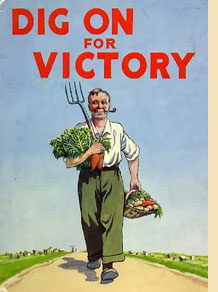

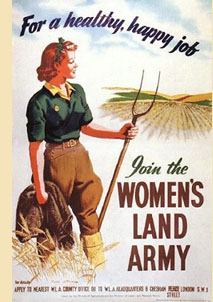

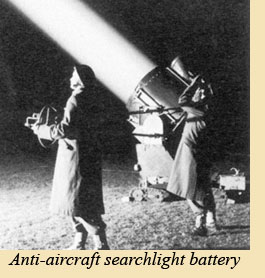

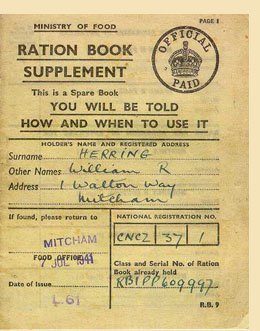

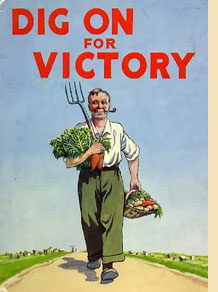

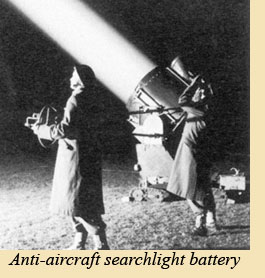

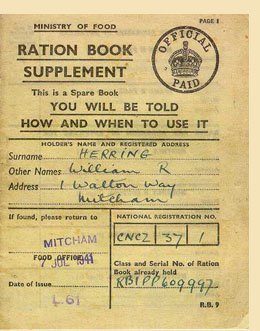

The village was, of course, a very different place during those years. Everyone had to contribute to the war effort. Men who were not required in important “reserved occupations” such as agriculture or aluminium production in Banbury were away in the armed forces. Women were required to “do their bit”, taking the place of the men on  farms and in nearby factories. Children helped in the fields, collected materials for recycling and picked wild berries. The school population was greatly increased by children evacuated from London and other cities to escape the bombing. The village had no piped water supply and therefore no sewerage system. Whilst there was a mains electricity supply it could be erratic and a strict blackout was enforced each night to avoid lights being seen by enemy aeroplanes. Travel was discouraged; there were few cars and petrol was in short supply. Food and many other essentials were rationed. Each household cultivated its own vegetables in gardens and allotments. Rabbits and pigeons were shot or snared to supplement the meat ration. A searchlight battery was located in the village and a prisoner of war camp nearby. Rumour was rife and only the BBC trusted for the latest information; people routinely gathered around their radios at nine o’clock each night hoping to learn the latest situation and perhaps something of their loved ones, often far away.

farms and in nearby factories. Children helped in the fields, collected materials for recycling and picked wild berries. The school population was greatly increased by children evacuated from London and other cities to escape the bombing. The village had no piped water supply and therefore no sewerage system. Whilst there was a mains electricity supply it could be erratic and a strict blackout was enforced each night to avoid lights being seen by enemy aeroplanes. Travel was discouraged; there were few cars and petrol was in short supply. Food and many other essentials were rationed. Each household cultivated its own vegetables in gardens and allotments. Rabbits and pigeons were shot or snared to supplement the meat ration. A searchlight battery was located in the village and a prisoner of war camp nearby. Rumour was rife and only the BBC trusted for the latest information; people routinely gathered around their radios at nine o’clock each night hoping to learn the latest situation and perhaps something of their loved ones, often far away.

Donald Taylor

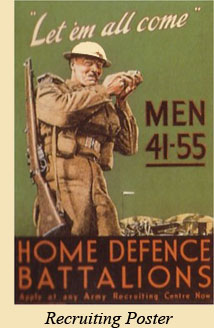

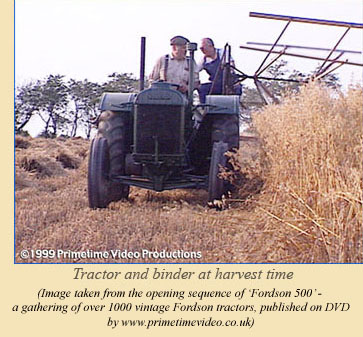

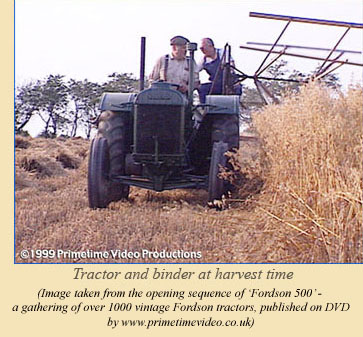

In 1939, I was almost 10 years old and used to working on the farm at haymaking and harvest. Dad joined the home guard and was commissioned as platoon commander. I was enthusiastic and would have joined but for my youth but I soon became familiar with the weapons issued to the home guard. Much fun has been made of this volunteer force e.g. Dad’s Army, but although poorly equipped they would have given a good account of themselves had the need arisen. In their own locality each H.G. unit could run rings round regular troops because of their intimate knowledge of the terrain and neighbourhood. This superiority was often demonstrated in exercises with other forces. At home we bought our first tractor in 1941 and I drove this at every opportunity, managing to become a reasonably proficient ploughman before my twelfth birthday (...and Donald is still ploughing! See here)

In 1939, I was almost 10 years old and used to working on the farm at haymaking and harvest. Dad joined the home guard and was commissioned as platoon commander. I was enthusiastic and would have joined but for my youth but I soon became familiar with the weapons issued to the home guard. Much fun has been made of this volunteer force e.g. Dad’s Army, but although poorly equipped they would have given a good account of themselves had the need arisen. In their own locality each H.G. unit could run rings round regular troops because of their intimate knowledge of the terrain and neighbourhood. This superiority was often demonstrated in exercises with other forces. At home we bought our first tractor in 1941 and I drove this at every opportunity, managing to become a reasonably proficient ploughman before my twelfth birthday (...and Donald is still ploughing! See here)

Donald Taylor's family and helpers haymaking

Lily Young

(My) bike had a lamp on the front which had to be blacked out, half, with brown paper. And then we had the soldiers up in the field, the Royal Artillery, with four searchlights  and when I was between here and Church Street, I used to hear them shout “Take post”, with these four big searchlights would come up like that, four of them. And I was talking to one of these boys one night and he said yes, one of these nights the German plane will come down the beam, and I said, “Thank you very much, and I shall probably be half way between here and home”.

and when I was between here and Church Street, I used to hear them shout “Take post”, with these four big searchlights would come up like that, four of them. And I was talking to one of these boys one night and he said yes, one of these nights the German plane will come down the beam, and I said, “Thank you very much, and I shall probably be half way between here and home”.

We had the troops up there, and then we had dances in the village, in the school room. Yes. Before the village hall. My mother was a pianist, she could play the piano by ear; she couldn’t read music properly. Of course there’s no lights, so when the home guard men were on top of the church she’d open her sitting room window, the curtains and the window, in the dark, and she’d play the piano to the men on the church.

One man we made friends with was in the Royal Artillery, Harold Budworth, he was a talented violinist and mother didn’t know that, you see. She used to play the piano for the dances and he said to her one night, he said, “Do you mind if I accompany you on my violin?” so she said “No, so long as you’re not talented”, “Oh, no, I’m not talented” he said, “I just play the violin”. He’d….got three or four letters after his name. He was a violin teacher. He was in the Hallé Orchestra before the war and he went back to it afterwards.

the dances and he said to her one night, he said, “Do you mind if I accompany you on my violin?” so she said “No, so long as you’re not talented”, “Oh, no, I’m not talented” he said, “I just play the violin”. He’d….got three or four letters after his name. He was a violin teacher. He was in the Hallé Orchestra before the war and he went back to it afterwards.

One night (my brother Jack said to me) “They’ve bombed Culworth”. That makes him (her husband John) laugh (because) he was in Portsmouth, he’s a Portsmouth boy and he’d go out to work in the morning and come out of his work and the street that was there had gone. So there was absolutely no comparison whatever to the towns ….. like ….. Portsmouth. They had the bombed dockyard and all that. We were all so frightened, to think they’d bombed Culworth … ‘course when I told him, he nearly had hysterics. We all know that Portsmouth suffered.

But the night they bombed Culworth will remain in Sulgrave history.

Roger Cherry

The German bombers used to come over here to bomb Coventry, which used to be a little bit worrying at times, but you got used to it and had to put up with it of course.

The German bombers used to come over here to bomb Coventry, which used to be a little bit worrying at times, but you got used to it and had to put up with it of course.

Occasionally there was a stray aircraft used to come round and probably dump his bombs around here because there was a stick of bombs went down the back of Culworth, right the way down – there was one in Ralph Taylor’s yard, one in John Harper’s, used to be next door, right down the – I think there were about seven or eight smallish bombs. They didn’t make a lot of damage but if you were underneath it wouldn’t be very pleasant at all.

Clearly most of the bombers passing over the village in 1940 were on their way to Coventry or other Midland industrial centres. Whilst not a resident of the village at that time, Bob Foster remembers the impact of this bombing on Coventry:

I was born in Coventry during the war and have quite strong memories at the end of the war about Coventry, and certainly I remember the state of Coventry after the war. I would have been four or five years old, and I remember the centre of Coventry. I remember the prefabricated shops that were put up temporarily to replace all the ones that were bombed, I remember the gaping great holes, which were the cellars of the shops and department stores in the centre of Coventry. Deep, deep holes in the ground which were the cellars of the old buildings, which had gone. And of course by the time I remember the rubble and the rubbish had all been cleared away, but it was completely devastated, and of course the Cathedral, which was synonymous with, almost an icon of, the blitz. There was a famous blitz on a particular night in Coventry – I think it was December 1940, which was long before I arrived, but there’s a photograph of the King and Queen visiting the empty shell of Coventry Cathedral, and the smouldering ruins.

I was born in Coventry during the war and have quite strong memories at the end of the war about Coventry, and certainly I remember the state of Coventry after the war. I would have been four or five years old, and I remember the centre of Coventry. I remember the prefabricated shops that were put up temporarily to replace all the ones that were bombed, I remember the gaping great holes, which were the cellars of the shops and department stores in the centre of Coventry. Deep, deep holes in the ground which were the cellars of the old buildings, which had gone. And of course by the time I remember the rubble and the rubbish had all been cleared away, but it was completely devastated, and of course the Cathedral, which was synonymous with, almost an icon of, the blitz. There was a famous blitz on a particular night in Coventry – I think it was December 1940, which was long before I arrived, but there’s a photograph of the King and Queen visiting the empty shell of Coventry Cathedral, and the smouldering ruins.

Coventry - 15th November 1940

Christopher Magnay

There was a search light detachment in the Glebe Field, which had dug-in search lights. (It was) surrounded by an embankment, and they had a light machine gun adapted for anti-aircraft mode, which I must say even I as a boy thought there wasn’t much chance of hitting anything with that. And I remember seeing it stuck on its tripod or bipod or whatever it was in the edge of this embankment and I thought, “Good gracious, you know, how’s that going to hit an aeroplane.” However, I don’t think it was ever fired in anger. It was probably more

There was a search light detachment in the Glebe Field, which had dug-in search lights. (It was) surrounded by an embankment, and they had a light machine gun adapted for anti-aircraft mode, which I must say even I as a boy thought there wasn’t much chance of hitting anything with that. And I remember seeing it stuck on its tripod or bipod or whatever it was in the edge of this embankment and I thought, “Good gracious, you know, how’s that going to hit an aeroplane.” However, I don’t think it was ever fired in anger. It was probably more dangerous for people in the village than it would have been for the Germans in the air. And the German aeroplanes used to come over to bomb Coventry and I suppose Birmingham, and we used to hear these funny engines, which had quite a different noise to English engines. A sort of burring noise and burbling. And we had an air-raid shelter built by the Wootton Brothers in our garden and I think it was only on one occasion were we persuaded to go down into the air-raid shelter. And I remember hearing these aeroplanes coming over and I think that was probably the night that they unloaded a bomb on Culworth and I think one of the aeroplanes had been hit, so it unloaded all its bombs before reaching the target. Or perhaps they were on their way back and hadn’t dropped all their bombs. One bomb hit a house in Culworth on the Thorpe Mandeville road and just beyond what was, until recently, the post office. And then I remember great excitement when a German aeroplane was shot down and landed in the field just by the Black Cottage on the Thorpe Mandeville – Culworth road, crashed into that field, and it hit the ground with such an impact that the wheels were picked up about 3 fields further on. I think that meant that the people in it were all killed.

dangerous for people in the village than it would have been for the Germans in the air. And the German aeroplanes used to come over to bomb Coventry and I suppose Birmingham, and we used to hear these funny engines, which had quite a different noise to English engines. A sort of burring noise and burbling. And we had an air-raid shelter built by the Wootton Brothers in our garden and I think it was only on one occasion were we persuaded to go down into the air-raid shelter. And I remember hearing these aeroplanes coming over and I think that was probably the night that they unloaded a bomb on Culworth and I think one of the aeroplanes had been hit, so it unloaded all its bombs before reaching the target. Or perhaps they were on their way back and hadn’t dropped all their bombs. One bomb hit a house in Culworth on the Thorpe Mandeville road and just beyond what was, until recently, the post office. And then I remember great excitement when a German aeroplane was shot down and landed in the field just by the Black Cottage on the Thorpe Mandeville – Culworth road, crashed into that field, and it hit the ground with such an impact that the wheels were picked up about 3 fields further on. I think that meant that the people in it were all killed.

Before the D-Day landings took place, we had this huge influx of soldiers into the area,  and we had Canadian troops billeted on our farm and in the village…..and all the roads were filled with vehicles going south, which was an extraordinary sight, I don’t know where they all came from but all sorts of vehicles, mainly English, British soldiers, and then when the actual D-Day landing took place we heard this extraordinary noise, all these aeroplanes going over, and they streamed over literally, as far as I remember, all night, and in the morning there was one – I’m not sure if it was the morning after D-Day but there was a tremendous explosion. I remember I was in bed and just thinking about getting up, and I suppose it was probably about half-past seven or something in the morning, and my curtains were drawn, and suddenly there was a terrific flash – it was in the summer – but even so, all the wall lit up, and then I thought, “What an extraordinary thing,” and then there was this huge bang, and I think a bomber had come down, crashed, near Whistley Wood, and exploded of course when it hit the ground.

and we had Canadian troops billeted on our farm and in the village…..and all the roads were filled with vehicles going south, which was an extraordinary sight, I don’t know where they all came from but all sorts of vehicles, mainly English, British soldiers, and then when the actual D-Day landing took place we heard this extraordinary noise, all these aeroplanes going over, and they streamed over literally, as far as I remember, all night, and in the morning there was one – I’m not sure if it was the morning after D-Day but there was a tremendous explosion. I remember I was in bed and just thinking about getting up, and I suppose it was probably about half-past seven or something in the morning, and my curtains were drawn, and suddenly there was a terrific flash – it was in the summer – but even so, all the wall lit up, and then I thought, “What an extraordinary thing,” and then there was this huge bang, and I think a bomber had come down, crashed, near Whistley Wood, and exploded of course when it hit the ground.

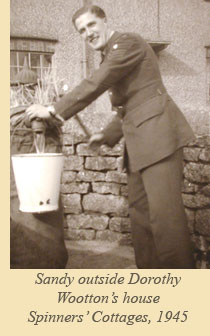

Sandy Munro

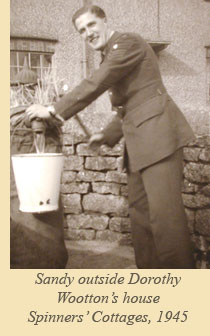

I first came to Sulgrave in 1943 when I was serving with the RAF and I was stationed at Chipping Warden, which was an operational training unit. They were full to the seams with

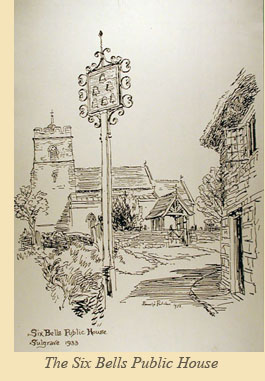

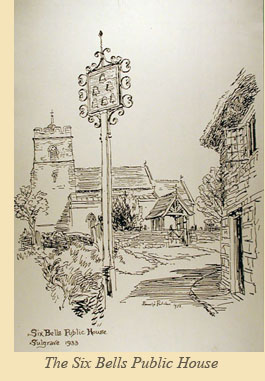

I first came to Sulgrave in 1943 when I was serving with the RAF and I was stationed at Chipping Warden, which was an operational training unit. They were full to the seams with  trainees and so they asked me, or they asked everybody, if they could find any billets outside the camp, grab it. And I happened to be over in Sulgrave in the Six Bells pub and I asked the Landlady, Mrs Newstead her name was, if she knew of anybody in this Parish who might have some accommodation that I could use and she said, well there’s a lady coming in very shortly, her husband has been killed, she’s a widow, he was the Clerk of Works at Chipping Warden Aerodrome and very tragically got killed in an accident there when the control tower was practically demolished by an aeroplane that didn’t get his sights right. Her first son had been a prisoner of war since February of 1940 when he was shot down in a Hampden aircraft and her second son had just joined the RAF. So she’d got a three bed-roomed house and I asked her when she came into the pub that evening and she said she’d be delighted and I went to live with her and lived there for, oh, six or seven months I suppose perhaps a little bit longer before I was posted somewhere else. Dorothy Wootton her name was and her son came back after the war and he actually occupied that house that I lived in.

trainees and so they asked me, or they asked everybody, if they could find any billets outside the camp, grab it. And I happened to be over in Sulgrave in the Six Bells pub and I asked the Landlady, Mrs Newstead her name was, if she knew of anybody in this Parish who might have some accommodation that I could use and she said, well there’s a lady coming in very shortly, her husband has been killed, she’s a widow, he was the Clerk of Works at Chipping Warden Aerodrome and very tragically got killed in an accident there when the control tower was practically demolished by an aeroplane that didn’t get his sights right. Her first son had been a prisoner of war since February of 1940 when he was shot down in a Hampden aircraft and her second son had just joined the RAF. So she’d got a three bed-roomed house and I asked her when she came into the pub that evening and she said she’d be delighted and I went to live with her and lived there for, oh, six or seven months I suppose perhaps a little bit longer before I was posted somewhere else. Dorothy Wootton her name was and her son came back after the war and he actually occupied that house that I lived in.

The reason I stayed in Sulgrave was …. it’s a romantic little story. After we’d been in that house at Number six Council Houses for some time, Mrs Wootton said to me - my niece is coming home from Reading where she’s working in a munitions factory. Now I think you’d like to meet her and I’d written to her and asked her if she’d like to meet us so we’re going to meet, not in the Six Bells but down in the Star. And so we went on the Saturday evening, down to the Star, and she said to me; the place was packed with soldiers and all sorts of RAF people; and she said ‘that’s my Niece just coming in the door’ and I looked at this young lady who was just coming in and I thought, oh, that’ll suit me, very well. And so we got together and did our old fashioned courtship and so on and I came back from time to time after I’d left this district and went up to … more or less … Lincolnshire was mainly where I was and we duly got married in December 8th, 1945. The wedding was up here at this Church and the reception was in the Six Bells clubroom, which was the room above the pub.

The reason I stayed in Sulgrave was …. it’s a romantic little story. After we’d been in that house at Number six Council Houses for some time, Mrs Wootton said to me - my niece is coming home from Reading where she’s working in a munitions factory. Now I think you’d like to meet her and I’d written to her and asked her if she’d like to meet us so we’re going to meet, not in the Six Bells but down in the Star. And so we went on the Saturday evening, down to the Star, and she said to me; the place was packed with soldiers and all sorts of RAF people; and she said ‘that’s my Niece just coming in the door’ and I looked at this young lady who was just coming in and I thought, oh, that’ll suit me, very well. And so we got together and did our old fashioned courtship and so on and I came back from time to time after I’d left this district and went up to … more or less … Lincolnshire was mainly where I was and we duly got married in December 8th, 1945. The wedding was up here at this Church and the reception was in the Six Bells clubroom, which was the room above the pub.

The club room above was quite big, quite probably, I don’t know, up to thirty feet long by about fifteen feet wide I suppose, and we had the reception there for about … I don’t know how many guests there were …. sixty or seventy, I suppose. Squeezed up in there somehow. And of course the catering was all done by locals. All people like Mrs Wootton and my family then knew of, and of course it was a … as you can imagine … a scratch meal put together, you know, with food and bits of bacon all they could get together, rationing being as it was in those days. So that was December 1945.

somehow. And of course the catering was all done by locals. All people like Mrs Wootton and my family then knew of, and of course it was a … as you can imagine … a scratch meal put together, you know, with food and bits of bacon all they could get together, rationing being as it was in those days. So that was December 1945.

I remember particularly, as far as we were concerned, the one thing we came to Sulgrave for, above everything else … there were two reasons I suppose … one was that the brewers in this area had the deliveries on different days and the word used to go ‘round that there was a beer delivery at Sulgrave today. It’s at the Six Bells this time, that was Halls Oxford brewery used to go there. The Star of course was Hook Norton brewery. So everybody knew on the camp where and when the brewers were going to deliver so we made a beeline for that particular village.

The other big reason for coming here was, down at Kiln Farm, which is where Phillip Henn now lives, there was a lady there who … she was married …. She and her husband kept … he was a farmer … name of Montgomery … and Mrs Montgomery used to serve most wonderful suppers. Home cured ham and eggs and chips and whatnot which we used to keep a low profile on, we never told anybody else … in case the place was packed out … and if you went to Mrs Montgomery say about half past seven or eight o’clock in the evening and she’d say, well, I’ve got six in or eight in now, when they’ve finished you can come and have yours meantime go up to the pub if its open have a drink and then come back down again. It was a wonderful … because it was so unusual to find somewhere, anywhere, where you could get that sort of meal. So we did that and of course never told anybody else. In case they had an influx. That was quite a thing.

Kiln Farm, where "Mrs Montgomery used to serve most wonderful suppers"

But of course as soon as the word got out ‘there was beer at so and so’ everybody, I mean everybody, I’m not talking about dozens I’m talking about hundreds … cycling…..and of course they’d drink them out, you know…..you see, this place was surrounded by army people. Search light battery up in the field just above the vicarage; the RASC at Culworth and the RAF at Chipping Warden, RAF at Silverstone, you see, and all these people were quite prepared to bicycle any distances if there was any beer to be had. So that’s how we used to survive then. Because the beer on a NAAFI canteen in these places was always pretty lousy. (Read more about Sandy and his wartime service).

Dennis Gascoigne (Farmer and Blacksmith’s son)

I left school the year the war started, in 1939. We converted the implements that they used with horses, to be behind the tractors for a start, because there was no machinery available. Ploughing was 70% of the farming, for the cause, for the war effort……we were dependent on imports as well, but the Government, you know, well they did the same in the First World War and of course it wasn’t on the scale of the Second and it was a matter of maximum food production, that was the aim.

I left school the year the war started, in 1939. We converted the implements that they used with horses, to be behind the tractors for a start, because there was no machinery available. Ploughing was 70% of the farming, for the cause, for the war effort……we were dependent on imports as well, but the Government, you know, well they did the same in the First World War and of course it wasn’t on the scale of the Second and it was a matter of maximum food production, that was the aim.

(Father) had to plough a bit of his field into corn, he didn’t like it, but there you are, every farm had to plough the land up to produce food, maximum food production, that was the aim. The only tractors you could get were the Fords…. a standard Fordson. They made it in the First World War actually and it went on to do 90% of the work in the Second World War…. it was quicker than a horse…because we’d only had horses before, just one furrow, that’s how it was done, but when they had to increase the arable acreage they had to have a tractor. So the demand for tractors was phenomenal. Henry Ford couldn’t make them fast enough, hardly, either. He built that new factory at Dagenham just before the war and that was on full production. I don’t know how many he made but you were limited to what you could have. David Brown started making tractors but he benefited from the lease-lend from President Roosevelt you know. The Americans agreed to send what they called lease-lend, they sent us new tractors over. The demand for tractors was such that when a Fordson was available in your area, the farmers drew lots to see who should have it. We had to have our Home Front as well as a War Front, you know. There were many people making aeroplanes and tanks and lorries and guns, and all the ammunition and all that, terrific job. So we were really grateful to the Americans for sending these lovely tractors over because they were about ten years ahead of us.

in the First World War actually and it went on to do 90% of the work in the Second World War…. it was quicker than a horse…because we’d only had horses before, just one furrow, that’s how it was done, but when they had to increase the arable acreage they had to have a tractor. So the demand for tractors was phenomenal. Henry Ford couldn’t make them fast enough, hardly, either. He built that new factory at Dagenham just before the war and that was on full production. I don’t know how many he made but you were limited to what you could have. David Brown started making tractors but he benefited from the lease-lend from President Roosevelt you know. The Americans agreed to send what they called lease-lend, they sent us new tractors over. The demand for tractors was such that when a Fordson was available in your area, the farmers drew lots to see who should have it. We had to have our Home Front as well as a War Front, you know. There were many people making aeroplanes and tanks and lorries and guns, and all the ammunition and all that, terrific job. So we were really grateful to the Americans for sending these lovely tractors over because they were about ten years ahead of us.

Dennis Gascoigne's father, George, at work in his Church Street Forge

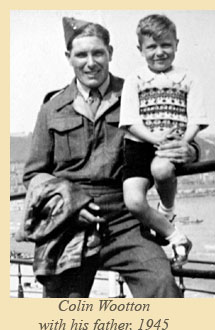

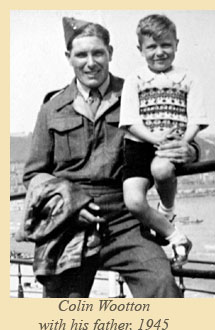

Colin Wootton

(I was seven years old when the war ended. My dad was in the infantry and I saw him very rarely and so just remember this khaki clad figure who would unexpectedly appear, pick me up and throw

(I was seven years old when the war ended. My dad was in the infantry and I saw him very rarely and so just remember this khaki clad figure who would unexpectedly appear, pick me up and throw me into the air despite my protests! He was stationed in Surrey at the time of the 1944 invasion) I was actually down there when, as they say, the balloon went up and I just remember ambulances, ambulances, ambulances coming back from the coast towards London, but getting there, to Surrey, you needed to go by train to London, and to get through London obviously and out to Surrey, where we stayed with him for a week and so we would walk to Peter’s bridge (on the road to Helmdon), scramble down the railway embankment, get on the railway, walk to the station (Helmdon) over the viaduct, hoping no trains came along.

me into the air despite my protests! He was stationed in Surrey at the time of the 1944 invasion) I was actually down there when, as they say, the balloon went up and I just remember ambulances, ambulances, ambulances coming back from the coast towards London, but getting there, to Surrey, you needed to go by train to London, and to get through London obviously and out to Surrey, where we stayed with him for a week and so we would walk to Peter’s bridge (on the road to Helmdon), scramble down the railway embankment, get on the railway, walk to the station (Helmdon) over the viaduct, hoping no trains came along.

And what I also remember of the train journey is coming back, at night, in the dark, everything was so dark, coming back through Bicester and little stations, people would say, ‘Where have we got to?’,you couldn’t tell, there’d be steam with everyone looking out of the windows and shouts and jumping out and the platform wasn’t actually there….

There were huge numbers of rabbits in the countryside; during the war, and just after and during rationing, they were very useful additions to the rations, as were pigeons. We consumed a huge amount of rabbits in pies, and pigeons likewise, as a boy, and so when the harvest time came, in a sense it was almost an attempt to harvest the rabbits. None were to be allowed to escape, if at all possible, and I can remember the field opposite Stuchbury (on the Helmdon Road) I don’t know if it’s ten or twenty acres or whatever it is, but I remember that we had 110 rabbits, which seems quite a lot, and the way that they were caught was that the ….binder that went round and round and left the sheaves, obviously and as it went round the unfortunate rabbits and all the other wild creatures retreated into the middle of the strip that was left so that when the final cut was made all hell broke loose because the creatures ran in all directions. Boys of the village were there armed with sticks, that they’d previously chosen, with a sort of knobbly end to use as clubs. There were also dogs of various descriptions and lots of guns and people shooting across one another and what-have-you. I saw somebody pepper his dog on one occasion; the dog was after, possibly, a hare and it was getting away. The role of the boys was basically to club these

None were to be allowed to escape, if at all possible, and I can remember the field opposite Stuchbury (on the Helmdon Road) I don’t know if it’s ten or twenty acres or whatever it is, but I remember that we had 110 rabbits, which seems quite a lot, and the way that they were caught was that the ….binder that went round and round and left the sheaves, obviously and as it went round the unfortunate rabbits and all the other wild creatures retreated into the middle of the strip that was left so that when the final cut was made all hell broke loose because the creatures ran in all directions. Boys of the village were there armed with sticks, that they’d previously chosen, with a sort of knobbly end to use as clubs. There were also dogs of various descriptions and lots of guns and people shooting across one another and what-have-you. I saw somebody pepper his dog on one occasion; the dog was after, possibly, a hare and it was getting away. The role of the boys was basically to club these  rabbits as they ran squealing in all directions. I had to take part in this and absolutely loathed it. Really did. I am far too tender hearted for anything like that but I had to do it and so, aiming at them and hopefully missing and things like that, they would run away from one (boy) and straight into another, so that they did tend to all get caught; and then they were all laid out in rows and they were shared out according to a sort of social pecking order. I remember this particular harvest for some reason, but it happened every year…going home sadly but proudly with a couple of rabbits with their legs tied on either end of the stick to my mother, who was equally tender hearted. However, as a village girl who’d grown up with a family of thirteen to feed, she was a good cook and pretty adept at dealing with things like that, so, at the sight of the rabbits she would shed tears….but…. she could skin a rabbit in about five minutes, it just used to sort of pop out of it’s skin….they were…. absolutely delicious. I haven’t eaten rabbit in this country, perhaps, since myxamotosis but I’ve had it in France..... I think it’s good. So she would put it in a stew, shall we say, with vegetables that had come from the garden, so in those days unlike to-day when we get the supermarket produce from all over the world, I reckon everything that we had to eat came from within a radius of probably about five miles.

rabbits as they ran squealing in all directions. I had to take part in this and absolutely loathed it. Really did. I am far too tender hearted for anything like that but I had to do it and so, aiming at them and hopefully missing and things like that, they would run away from one (boy) and straight into another, so that they did tend to all get caught; and then they were all laid out in rows and they were shared out according to a sort of social pecking order. I remember this particular harvest for some reason, but it happened every year…going home sadly but proudly with a couple of rabbits with their legs tied on either end of the stick to my mother, who was equally tender hearted. However, as a village girl who’d grown up with a family of thirteen to feed, she was a good cook and pretty adept at dealing with things like that, so, at the sight of the rabbits she would shed tears….but…. she could skin a rabbit in about five minutes, it just used to sort of pop out of it’s skin….they were…. absolutely delicious. I haven’t eaten rabbit in this country, perhaps, since myxamotosis but I’ve had it in France..... I think it’s good. So she would put it in a stew, shall we say, with vegetables that had come from the garden, so in those days unlike to-day when we get the supermarket produce from all over the world, I reckon everything that we had to eat came from within a radius of probably about five miles.

(My uncle and auntie lived in one of the Stuchbury cottages on the road to Helmdon, which had no electricity, drainage or piped water and where I spent many happy Christmases) I remember the house as being very comfortable in the old fashioned style  because, in the days when there were still elm trees which always dropped limbs very readily, every day (as my uncle walked to his work on the nearby farm), or on the way back, perhaps after he’s walked home for some lunch, he carried a fallen limb, and I can see them now,

because, in the days when there were still elm trees which always dropped limbs very readily, every day (as my uncle walked to his work on the nearby farm), or on the way back, perhaps after he’s walked home for some lunch, he carried a fallen limb, and I can see them now, stacked outside the cottage and some weekend part of his work would be to saw them up so they had lots of wood for the winter, it’s not the best of wood to burn but it was readily available and he had a large garden in which he grew everything you could think of. The potatoes, I particularly remember, were clamped, in other words they were piled up on the ground that they’d been dug from and covered in straw and then earthed over, so that there was a winter’s supply. Carrots were put in sand. Auntie Annie bottled everything that could be bottled. Without any electricity their radio had accumulator batteries - they were big and they were obviously glass cells with presumably sulphuric acid and lead in, which had to go off somewhere to be recharged, because pre-transistors the radios had valves which took a lot of electricity to run. Light was provided in the main room by a paraffin lamp burning with a mantle, and it was tremendously efficient and it gave out a huge amount of light and so I don’t remember it being problematic to stay there. There were candles obviously for going to bed and….so they lived a life that reflected what the village as a whole would have been like quite a few years before that.

stacked outside the cottage and some weekend part of his work would be to saw them up so they had lots of wood for the winter, it’s not the best of wood to burn but it was readily available and he had a large garden in which he grew everything you could think of. The potatoes, I particularly remember, were clamped, in other words they were piled up on the ground that they’d been dug from and covered in straw and then earthed over, so that there was a winter’s supply. Carrots were put in sand. Auntie Annie bottled everything that could be bottled. Without any electricity their radio had accumulator batteries - they were big and they were obviously glass cells with presumably sulphuric acid and lead in, which had to go off somewhere to be recharged, because pre-transistors the radios had valves which took a lot of electricity to run. Light was provided in the main room by a paraffin lamp burning with a mantle, and it was tremendously efficient and it gave out a huge amount of light and so I don’t remember it being problematic to stay there. There were candles obviously for going to bed and….so they lived a life that reflected what the village as a whole would have been like quite a few years before that.

TOP

The village was, of course, a very different place during those years. Everyone had to contribute to the war effort. Men who were not required in important “reserved occupations” such as agriculture or aluminium production in Banbury were away in the armed forces. Women were required to “do their bit”, taking the place of the men on

The village was, of course, a very different place during those years. Everyone had to contribute to the war effort. Men who were not required in important “reserved occupations” such as agriculture or aluminium production in Banbury were away in the armed forces. Women were required to “do their bit”, taking the place of the men on  farms and in nearby factories. Children helped in the fields, collected materials for recycling and picked wild berries. The school population was greatly increased by children evacuated from London and other cities to escape the bombing. The village had no piped water supply and therefore no sewerage system. Whilst there was a mains electricity supply it could be erratic and a strict blackout was enforced each night to avoid lights being seen by enemy aeroplanes. Travel was discouraged; there were few cars and petrol was in short supply. Food and many other essentials were rationed. Each household cultivated its own vegetables in gardens and allotments. Rabbits and pigeons were shot or snared to supplement the meat ration. A searchlight battery was located in the village and a prisoner of war camp nearby. Rumour was rife and only the BBC trusted for the latest information; people routinely gathered around their radios at nine o’clock each night hoping to learn the latest situation and perhaps something of their loved ones, often far away.

farms and in nearby factories. Children helped in the fields, collected materials for recycling and picked wild berries. The school population was greatly increased by children evacuated from London and other cities to escape the bombing. The village had no piped water supply and therefore no sewerage system. Whilst there was a mains electricity supply it could be erratic and a strict blackout was enforced each night to avoid lights being seen by enemy aeroplanes. Travel was discouraged; there were few cars and petrol was in short supply. Food and many other essentials were rationed. Each household cultivated its own vegetables in gardens and allotments. Rabbits and pigeons were shot or snared to supplement the meat ration. A searchlight battery was located in the village and a prisoner of war camp nearby. Rumour was rife and only the BBC trusted for the latest information; people routinely gathered around their radios at nine o’clock each night hoping to learn the latest situation and perhaps something of their loved ones, often far away. In 1939, I was almost 10 years old and used to working on the farm at haymaking and harvest. Dad joined the home guard and was commissioned as platoon commander. I was enthusiastic and would have joined but for my youth but I soon became familiar with the weapons issued to the home guard. Much fun has been made of this volunteer force e.g. Dad’s Army, but although poorly equipped they would have given a good account of themselves had the need arisen. In their own locality each H.G. unit could run rings round regular troops because of their intimate knowledge of the terrain and neighbourhood. This superiority was often demonstrated in exercises with other forces. At home we bought our first tractor in 1941 and I drove this at every opportunity, managing to become a reasonably proficient ploughman before my twelfth birthday (...and Donald is still ploughing!

In 1939, I was almost 10 years old and used to working on the farm at haymaking and harvest. Dad joined the home guard and was commissioned as platoon commander. I was enthusiastic and would have joined but for my youth but I soon became familiar with the weapons issued to the home guard. Much fun has been made of this volunteer force e.g. Dad’s Army, but although poorly equipped they would have given a good account of themselves had the need arisen. In their own locality each H.G. unit could run rings round regular troops because of their intimate knowledge of the terrain and neighbourhood. This superiority was often demonstrated in exercises with other forces. At home we bought our first tractor in 1941 and I drove this at every opportunity, managing to become a reasonably proficient ploughman before my twelfth birthday (...and Donald is still ploughing!

and when I was between here and Church Street, I used to hear them shout “Take post”, with these four big searchlights would come up like that, four of them. And I was talking to one of these boys one night and he said yes, one of these nights the German plane will come down the beam, and I said, “Thank you very much, and I shall probably be half way between here and home”.

and when I was between here and Church Street, I used to hear them shout “Take post”, with these four big searchlights would come up like that, four of them. And I was talking to one of these boys one night and he said yes, one of these nights the German plane will come down the beam, and I said, “Thank you very much, and I shall probably be half way between here and home”. the dances and he said to her one night, he said, “Do you mind if I accompany you on my violin?” so she said “No, so long as you’re not talented”, “Oh, no, I’m not talented” he said, “I just play the violin”. He’d….got three or four letters after his name. He was a violin teacher. He was in the Hallé Orchestra before the war and he went back to it afterwards.

the dances and he said to her one night, he said, “Do you mind if I accompany you on my violin?” so she said “No, so long as you’re not talented”, “Oh, no, I’m not talented” he said, “I just play the violin”. He’d….got three or four letters after his name. He was a violin teacher. He was in the Hallé Orchestra before the war and he went back to it afterwards. The German bombers used to come over here to bomb Coventry, which used to be a little bit worrying at times, but you got used to it and had to put up with it of course.

The German bombers used to come over here to bomb Coventry, which used to be a little bit worrying at times, but you got used to it and had to put up with it of course.  I was born in Coventry during the war and have quite strong memories at the end of the war about Coventry, and certainly I remember the state of Coventry after the war. I would have been four or five years old, and I remember the centre of Coventry. I remember the prefabricated shops that were put up temporarily to replace all the ones that were bombed, I remember the gaping great holes, which were the cellars of the shops and department stores in the centre of Coventry. Deep, deep holes in the ground which were the cellars of the old buildings, which had gone. And of course by the time I remember the rubble and the rubbish had all been cleared away, but it was completely devastated, and of course the Cathedral, which was synonymous with, almost an icon of, the blitz. There was a famous blitz on a particular night in Coventry – I think it was December 1940, which was long before I arrived, but there’s a photograph of the King and Queen visiting the empty shell of Coventry Cathedral, and the smouldering ruins.

I was born in Coventry during the war and have quite strong memories at the end of the war about Coventry, and certainly I remember the state of Coventry after the war. I would have been four or five years old, and I remember the centre of Coventry. I remember the prefabricated shops that were put up temporarily to replace all the ones that were bombed, I remember the gaping great holes, which were the cellars of the shops and department stores in the centre of Coventry. Deep, deep holes in the ground which were the cellars of the old buildings, which had gone. And of course by the time I remember the rubble and the rubbish had all been cleared away, but it was completely devastated, and of course the Cathedral, which was synonymous with, almost an icon of, the blitz. There was a famous blitz on a particular night in Coventry – I think it was December 1940, which was long before I arrived, but there’s a photograph of the King and Queen visiting the empty shell of Coventry Cathedral, and the smouldering ruins.

There was a search light detachment in the Glebe Field, which had dug-in search lights.

There was a search light detachment in the Glebe Field, which had dug-in search lights.  dangerous for people in the village than it would have been for the Germans in the air. And the German aeroplanes used to come over to bomb Coventry and I suppose Birmingham, and we used to hear these funny engines, which had quite a different noise to English engines. A sort of burring noise and burbling. And we had an air-raid shelter built by the Wootton Brothers in our garden and I think it was only on one occasion were we persuaded to go down into the air-raid shelter. And I remember hearing these aeroplanes coming over and I think that was probably the night that they unloaded a bomb on Culworth and I think one of the aeroplanes had been hit, so it unloaded all its bombs before reaching the target. Or perhaps they were on their way back and hadn’t dropped all their bombs. One bomb hit a house in Culworth on the Thorpe Mandeville road and just beyond what was, until recently, the post office. And then I remember great excitement when a German aeroplane was shot down and landed in the field just by the Black Cottage on the Thorpe Mandeville – Culworth road, crashed into that field, and it hit the ground with such an impact that the wheels were picked up about 3 fields further on. I think that meant that the people in it were all killed.

dangerous for people in the village than it would have been for the Germans in the air. And the German aeroplanes used to come over to bomb Coventry and I suppose Birmingham, and we used to hear these funny engines, which had quite a different noise to English engines. A sort of burring noise and burbling. And we had an air-raid shelter built by the Wootton Brothers in our garden and I think it was only on one occasion were we persuaded to go down into the air-raid shelter. And I remember hearing these aeroplanes coming over and I think that was probably the night that they unloaded a bomb on Culworth and I think one of the aeroplanes had been hit, so it unloaded all its bombs before reaching the target. Or perhaps they were on their way back and hadn’t dropped all their bombs. One bomb hit a house in Culworth on the Thorpe Mandeville road and just beyond what was, until recently, the post office. And then I remember great excitement when a German aeroplane was shot down and landed in the field just by the Black Cottage on the Thorpe Mandeville – Culworth road, crashed into that field, and it hit the ground with such an impact that the wheels were picked up about 3 fields further on. I think that meant that the people in it were all killed. and we had Canadian troops billeted on our farm and in the village…..and all the roads were filled with vehicles going south, which was an extraordinary sight, I don’t know where they all came from but all sorts of vehicles, mainly English, British soldiers, and then when the actual D-Day landing took place we heard this extraordinary noise, all these aeroplanes going over, and they streamed over literally, as far as I remember, all night, and in the morning there was one – I’m not sure if it was the morning after D-Day but there was a tremendous explosion. I remember I was in bed and just thinking about getting up, and I suppose it was probably about half-past seven or something in the morning, and my curtains were drawn, and suddenly there was a terrific flash – it was in the summer – but even so, all the wall lit up, and then I thought, “What an extraordinary thing,” and then there was this huge bang, and I think a bomber had come down, crashed, near Whistley Wood, and exploded of course when it hit the ground.

and we had Canadian troops billeted on our farm and in the village…..and all the roads were filled with vehicles going south, which was an extraordinary sight, I don’t know where they all came from but all sorts of vehicles, mainly English, British soldiers, and then when the actual D-Day landing took place we heard this extraordinary noise, all these aeroplanes going over, and they streamed over literally, as far as I remember, all night, and in the morning there was one – I’m not sure if it was the morning after D-Day but there was a tremendous explosion. I remember I was in bed and just thinking about getting up, and I suppose it was probably about half-past seven or something in the morning, and my curtains were drawn, and suddenly there was a terrific flash – it was in the summer – but even so, all the wall lit up, and then I thought, “What an extraordinary thing,” and then there was this huge bang, and I think a bomber had come down, crashed, near Whistley Wood, and exploded of course when it hit the ground. trainees and so they asked me, or they asked everybody, if they could find any billets outside the camp, grab it. And I happened to be over in Sulgrave in the Six Bells pub and I asked the Landlady, Mrs Newstead her name was, if she knew of anybody in this Parish who might have some accommodation that I could use and she said, well there’s a lady coming in very shortly, her husband has been killed, she’s a widow, he was the Clerk of Works at Chipping Warden Aerodrome and very tragically got killed in an accident there when the control tower was practically demolished by an aeroplane that didn’t get his sights right. Her first son had been a prisoner of war since February of 1940 when he was shot down in a Hampden aircraft and her second son had just joined the RAF. So she’d got a three bed-roomed house and I asked her when she came into the pub that evening and she said she’d be delighted and I went to live with her and lived there for, oh, six or seven months I suppose perhaps a little bit longer before I was posted somewhere else. Dorothy Wootton her name was and her son came back after the war and he actually occupied that house that I lived in.

trainees and so they asked me, or they asked everybody, if they could find any billets outside the camp, grab it. And I happened to be over in Sulgrave in the Six Bells pub and I asked the Landlady, Mrs Newstead her name was, if she knew of anybody in this Parish who might have some accommodation that I could use and she said, well there’s a lady coming in very shortly, her husband has been killed, she’s a widow, he was the Clerk of Works at Chipping Warden Aerodrome and very tragically got killed in an accident there when the control tower was practically demolished by an aeroplane that didn’t get his sights right. Her first son had been a prisoner of war since February of 1940 when he was shot down in a Hampden aircraft and her second son had just joined the RAF. So she’d got a three bed-roomed house and I asked her when she came into the pub that evening and she said she’d be delighted and I went to live with her and lived there for, oh, six or seven months I suppose perhaps a little bit longer before I was posted somewhere else. Dorothy Wootton her name was and her son came back after the war and he actually occupied that house that I lived in. The reason I stayed in Sulgrave was …. it’s a romantic little story. After we’d been in that house at Number six Council Houses for some time, Mrs Wootton said to me - my niece is coming home from Reading where she’s working in a munitions factory. Now I think you’d like to meet her and I’d written to her and asked her if she’d like to meet us so we’re going to meet, not in the Six Bells but down in the Star. And so we went on the Saturday evening, down to the Star, and she said to me; the place was packed with soldiers and all sorts of RAF people; and she said ‘that’s my Niece just coming in the door’ and I looked at this young lady who was just coming in and I thought, oh, that’ll suit me, very well. And so we got together and did our old fashioned courtship and so on and I came back from time to time after I’d left this district and went up to … more or less … Lincolnshire was mainly where I was and we duly got married in December 8th, 1945. The wedding was up here at this Church and the reception was in the Six Bells clubroom, which was the room above the pub.

The reason I stayed in Sulgrave was …. it’s a romantic little story. After we’d been in that house at Number six Council Houses for some time, Mrs Wootton said to me - my niece is coming home from Reading where she’s working in a munitions factory. Now I think you’d like to meet her and I’d written to her and asked her if she’d like to meet us so we’re going to meet, not in the Six Bells but down in the Star. And so we went on the Saturday evening, down to the Star, and she said to me; the place was packed with soldiers and all sorts of RAF people; and she said ‘that’s my Niece just coming in the door’ and I looked at this young lady who was just coming in and I thought, oh, that’ll suit me, very well. And so we got together and did our old fashioned courtship and so on and I came back from time to time after I’d left this district and went up to … more or less … Lincolnshire was mainly where I was and we duly got married in December 8th, 1945. The wedding was up here at this Church and the reception was in the Six Bells clubroom, which was the room above the pub. somehow. And of course the catering was all done by locals. All people like Mrs Wootton and my family then knew of, and of course it was a … as you can imagine … a scratch meal put together, you know, with food and bits of bacon all they could get together, rationing being as it was in those days. So that was December 1945.

somehow. And of course the catering was all done by locals. All people like Mrs Wootton and my family then knew of, and of course it was a … as you can imagine … a scratch meal put together, you know, with food and bits of bacon all they could get together, rationing being as it was in those days. So that was December 1945.

I left school the year the war started, in 1939. We converted the implements that they used with horses, to be behind the tractors for a start, because there was no machinery available. Ploughing was 70% of the farming, for the cause, for the war effort……we were dependent on imports as well, but the Government, you know, well they did the same in the First World War and of course it wasn’t on the scale of the Second and it was a matter of maximum food production, that was the aim.

I left school the year the war started, in 1939. We converted the implements that they used with horses, to be behind the tractors for a start, because there was no machinery available. Ploughing was 70% of the farming, for the cause, for the war effort……we were dependent on imports as well, but the Government, you know, well they did the same in the First World War and of course it wasn’t on the scale of the Second and it was a matter of maximum food production, that was the aim. in the First World War actually and it went on to do 90% of the work in the Second World War…. it was quicker than a horse…because we’d only had horses before, just one furrow, that’s how it was done, but when they had to increase the arable acreage they had to have a tractor. So the demand for tractors was phenomenal. Henry Ford couldn’t make them fast enough, hardly, either. He built that new factory at Dagenham just before the war and that was on full production. I don’t know how many he made but you were limited to what you could have. David Brown started making tractors but he benefited from the lease-lend from President Roosevelt you know. The Americans agreed to send what they called lease-lend, they sent us new tractors over. The demand for tractors was such that when a Fordson was available in your area, the farmers drew lots to see who should have it. We had to have our Home Front as well as a War Front, you know. There were many people making aeroplanes and tanks and lorries and guns, and all the ammunition and all that, terrific job. So we were really grateful to the Americans for sending these lovely tractors over because they were about ten years ahead of us.

in the First World War actually and it went on to do 90% of the work in the Second World War…. it was quicker than a horse…because we’d only had horses before, just one furrow, that’s how it was done, but when they had to increase the arable acreage they had to have a tractor. So the demand for tractors was phenomenal. Henry Ford couldn’t make them fast enough, hardly, either. He built that new factory at Dagenham just before the war and that was on full production. I don’t know how many he made but you were limited to what you could have. David Brown started making tractors but he benefited from the lease-lend from President Roosevelt you know. The Americans agreed to send what they called lease-lend, they sent us new tractors over. The demand for tractors was such that when a Fordson was available in your area, the farmers drew lots to see who should have it. We had to have our Home Front as well as a War Front, you know. There were many people making aeroplanes and tanks and lorries and guns, and all the ammunition and all that, terrific job. So we were really grateful to the Americans for sending these lovely tractors over because they were about ten years ahead of us.

(I was seven years old when the war ended. My dad was in the infantry and I saw him very rarely and so just remember this khaki clad figure who would unexpectedly appear, pick me up and throw

(I was seven years old when the war ended. My dad was in the infantry and I saw him very rarely and so just remember this khaki clad figure who would unexpectedly appear, pick me up and throw me into the air despite my protests! He was stationed in Surrey at the time of the 1944 invasion) I was actually down there when, as they say, the balloon went up and I just remember ambulances, ambulances, ambulances coming back from the coast towards London, but getting there, to Surrey, you needed to go by train to London, and to get through London obviously and out to Surrey, where we stayed with him for a week and so we would walk to Peter’s bridge (on the road to Helmdon), scramble down the railway embankment, get on the railway, walk to the station (Helmdon) over the viaduct, hoping no trains came along.

me into the air despite my protests! He was stationed in Surrey at the time of the 1944 invasion) I was actually down there when, as they say, the balloon went up and I just remember ambulances, ambulances, ambulances coming back from the coast towards London, but getting there, to Surrey, you needed to go by train to London, and to get through London obviously and out to Surrey, where we stayed with him for a week and so we would walk to Peter’s bridge (on the road to Helmdon), scramble down the railway embankment, get on the railway, walk to the station (Helmdon) over the viaduct, hoping no trains came along. None were to be allowed to escape, if at all possible, and I can remember the field opposite Stuchbury (on the Helmdon Road) I don’t know if it’s ten or twenty acres or whatever it is, but I remember that we had 110 rabbits, which seems quite a lot, and the way that they were caught was that the ….binder that went round and round and left the sheaves, obviously and as it went round the unfortunate rabbits and all the other wild creatures retreated into the middle of the strip that was left so that when the final cut was made all hell broke loose because the creatures ran in all directions. Boys of the village were there armed with sticks, that they’d previously chosen, with a sort of knobbly end to use as clubs. There were also dogs of various descriptions and lots of guns and people shooting across one another and what-have-you. I saw somebody pepper his dog on one occasion; the dog was after, possibly, a hare and it was getting away. The role of the boys was basically to club these

None were to be allowed to escape, if at all possible, and I can remember the field opposite Stuchbury (on the Helmdon Road) I don’t know if it’s ten or twenty acres or whatever it is, but I remember that we had 110 rabbits, which seems quite a lot, and the way that they were caught was that the ….binder that went round and round and left the sheaves, obviously and as it went round the unfortunate rabbits and all the other wild creatures retreated into the middle of the strip that was left so that when the final cut was made all hell broke loose because the creatures ran in all directions. Boys of the village were there armed with sticks, that they’d previously chosen, with a sort of knobbly end to use as clubs. There were also dogs of various descriptions and lots of guns and people shooting across one another and what-have-you. I saw somebody pepper his dog on one occasion; the dog was after, possibly, a hare and it was getting away. The role of the boys was basically to club these  rabbits as they ran squealing in all directions. I had to take part in this and absolutely loathed it. Really did. I am far too tender hearted for anything like that but I had to do it and so, aiming at them and hopefully missing and things like that, they would run away from one (boy) and straight into another, so that they did tend to all get caught; and then they were all laid out in rows and they were shared out according to a sort of social pecking order. I remember this particular harvest for some reason, but it happened every year…going home sadly but proudly with a couple of rabbits with their legs tied on either end of the stick to my mother, who was equally tender hearted. However, as a village girl who’d grown up with a family of thirteen to feed, she was a good cook and pretty adept at dealing with things like that, so, at the sight of the rabbits she would shed tears….but…. she could skin a rabbit in about five minutes, it just used to sort of pop out of it’s skin….they were…. absolutely delicious. I haven’t eaten rabbit in this country, perhaps, since myxamotosis but I’ve had it in France..... I think it’s good. So she would put it in a stew, shall we say, with vegetables that had come from the garden, so in those days unlike to-day when we get the supermarket produce from all over the world, I reckon everything that we had to eat came from within a radius of probably about five miles.

rabbits as they ran squealing in all directions. I had to take part in this and absolutely loathed it. Really did. I am far too tender hearted for anything like that but I had to do it and so, aiming at them and hopefully missing and things like that, they would run away from one (boy) and straight into another, so that they did tend to all get caught; and then they were all laid out in rows and they were shared out according to a sort of social pecking order. I remember this particular harvest for some reason, but it happened every year…going home sadly but proudly with a couple of rabbits with their legs tied on either end of the stick to my mother, who was equally tender hearted. However, as a village girl who’d grown up with a family of thirteen to feed, she was a good cook and pretty adept at dealing with things like that, so, at the sight of the rabbits she would shed tears….but…. she could skin a rabbit in about five minutes, it just used to sort of pop out of it’s skin….they were…. absolutely delicious. I haven’t eaten rabbit in this country, perhaps, since myxamotosis but I’ve had it in France..... I think it’s good. So she would put it in a stew, shall we say, with vegetables that had come from the garden, so in those days unlike to-day when we get the supermarket produce from all over the world, I reckon everything that we had to eat came from within a radius of probably about five miles. because, in the days when there were still elm trees which always dropped limbs very readily, every day (as my uncle walked to his work on the nearby farm), or on the way back, perhaps after he’s walked home for some lunch, he carried a fallen limb, and I can see them now,

because, in the days when there were still elm trees which always dropped limbs very readily, every day (as my uncle walked to his work on the nearby farm), or on the way back, perhaps after he’s walked home for some lunch, he carried a fallen limb, and I can see them now, stacked outside the cottage and some weekend part of his work would be to saw them up so they had lots of wood for the winter, it’s not the best of wood to burn but it was readily available and he had a large garden in which he grew everything you could think of. The potatoes, I particularly remember, were clamped, in other words they were piled up on the ground that they’d been dug from and covered in straw and then earthed over, so that there was a winter’s supply. Carrots were put in sand. Auntie Annie bottled everything that could be bottled. Without any electricity their radio had accumulator batteries - they were big and they were obviously glass cells with presumably sulphuric acid and lead in, which had to go off somewhere to be recharged, because pre-transistors the radios had valves which took a lot of electricity to run. Light was provided in the main room by a paraffin lamp burning with a mantle, and it was tremendously efficient and it gave out a huge amount of light and so I don’t remember it being problematic to stay there. There were candles obviously for going to bed and….so they lived a life that reflected what the village as a whole would have been like quite a few years before that.

stacked outside the cottage and some weekend part of his work would be to saw them up so they had lots of wood for the winter, it’s not the best of wood to burn but it was readily available and he had a large garden in which he grew everything you could think of. The potatoes, I particularly remember, were clamped, in other words they were piled up on the ground that they’d been dug from and covered in straw and then earthed over, so that there was a winter’s supply. Carrots were put in sand. Auntie Annie bottled everything that could be bottled. Without any electricity their radio had accumulator batteries - they were big and they were obviously glass cells with presumably sulphuric acid and lead in, which had to go off somewhere to be recharged, because pre-transistors the radios had valves which took a lot of electricity to run. Light was provided in the main room by a paraffin lamp burning with a mantle, and it was tremendously efficient and it gave out a huge amount of light and so I don’t remember it being problematic to stay there. There were candles obviously for going to bed and….so they lived a life that reflected what the village as a whole would have been like quite a few years before that.