MEMORIES OF WARTIME SULGRAVE by JOHN SMITH

(EVACUATED TO THE VILLAGE FROM LONDON IN 1939)

(Home)

At 11am on September 3rd 1939 I was, age nine, with the rest of the family sitting in the living room of our semi in a London suburb, listening to the Prime Minister on the radio. We had no air raid shelter so a mattress covered the doors leading to the garden and the windows in the doors had paper strips stuck to them to prevent (we hoped) the glass being shattered by bomb blast. We probably had our gas masks close at hand. With these simple precautions we were ready to face the unknown. My father was a milkman and he had interrupted his deliveries to listen to the Prime Minister and I well remember the Prime Minister’s solemn tones. But, war or no war, life had to go on and I accompanied my Father when he took his horse drawn milk float back to the depot. Within minutes we saw the barrage balloons beginning to ascend closely followed by the wail of the air raid warning. We continued our journey only to be stopped by a policeman, wearing a steel helmet in place of the traditional headgear, who instructed us to take cover, whereupon my father asked “What about the horse?” Faced with this situation the policeman agreed that we should proceed to the dairy yard as quickly as possible.

deliveries to listen to the Prime Minister and I well remember the Prime Minister’s solemn tones. But, war or no war, life had to go on and I accompanied my Father when he took his horse drawn milk float back to the depot. Within minutes we saw the barrage balloons beginning to ascend closely followed by the wail of the air raid warning. We continued our journey only to be stopped by a policeman, wearing a steel helmet in place of the traditional headgear, who instructed us to take cover, whereupon my father asked “What about the horse?” Faced with this situation the policeman agreed that we should proceed to the dairy yard as quickly as possible.

Within a matter of days my sister and I were evacuated to live with relatives, Butchers and Woottons at Stuchbury. This was a turning point in my life. From being a town boy I was to became a country boy, although I did not realise it at the time, and have been a bit of both ever since.

There were no air raid warnings or air raid shelters. I doubt whether there were any air raid shelters in Sulgrave, let alone Stuchbury, and the nearest barrage balloon was probably fifty miles away.

It was a dramatically different life, but one which I seemed to adapt to easily. We lived in a small cottage with my Aunt, her sister and husband (who was the tenant), a baby of a few months and four children between five and nine years. It was crowded. Water came from a hand operated pump at the front of the cottage or from the water tubs which collected rainwater from the roof. There was no electricity and light was provided by oil lamps and candles. The main living room was also the kitchen where a solid fuel stove provided heat for cooking all year round and room heating in the winter. There was rarely any other heat in the house, although there was a fireplace in the small “front room”, but I seem to recall that this room was only used at Christmas and on some Sundays. The kitchen stove was the only source of heat to boil a kettle year round. There was no heating in the upper rooms and three or four children sleeping in one small room meant that on cold nights the windows were soon covered in condensation and on frosty nights ‘Jack Frost’ converted this moisture into intricate icy patterns. I remember that the kitchen stove burnt wood , but perhaps it also burnt coal. The same method of heating was employed for a ‘copper’ to heat water for washing clothes and bed linen and to provide hot water for a bath, which might have been a weekly event, but could have been at longer intervals. One of the jobs of the children was to go out to collect firewood after a storm had blown dead wood out of the trees. There was no sewage and the loo at the bottom of the garden was basic - a large bucket which was emptied once a week into a pit, also in the garden.

Perhaps there was no radio in the cottage or if there was one it would have been powered by a battery. I don’t remember a radio providing entertainment in the evenings, but I do remember playing table games and cards around an oil lamp on winter evenings.

Life wasn’t always easy for a working class family in a London suburb, but this was altogether different.

No buses passing the end of the road every ten or fifteen minutes, no shopping street within fifteen or twenty minutes walk, no newspaper landing on the mat before breakfast every morning…….

One green bus passed by Stuchbury on Wednesday each week en route to Northampton returning later the same day; just one shop in Sulgrave and the butcher called once a week; a newspaper was wedged in the gate at the end of the lane sometime around mid day and the nights were extremely dark and quiet.

At home there were some open spaces covered with grass and flower beds called parks, among the streets and houses, where games could be played. For me, Stuchbury was surrounded by one enormous park populated by a few animals and with no park keepers. Plenty of space and freedom for games and exploring – it seemed a good arrangement to me.

I had been transplanted from a suburban industrial and commuting community to a relatively isolated and almost exclusively agricultural community where life was dictated by the seasons and the weather. This might have been a shock for some evacuees, but I was within the extended family and that probably helped me to adapt. I learnt that milk didn’t come in bottles but was collected, unpastuerised, in a tin plated one pint reusable can from the farm. I remember that it was a treat to have a milk pudding made from the rich milk given by a cow after the birth of a calf; for some strange reason this milk was called ‘cherry curds’, or is my memory playing tricks?

I had come from a Junior Elementary school with several hundred pupils split into classes by age. An Infant school and a Senior

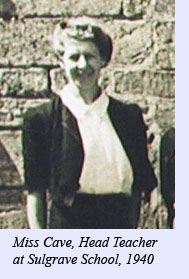

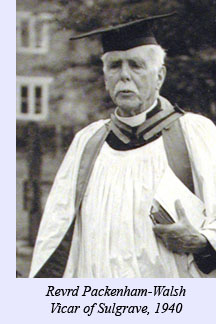

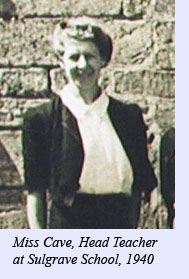

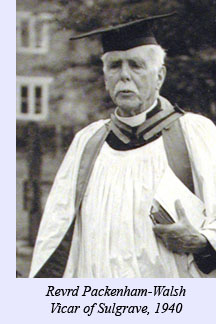

I had come from a Junior Elementary school with several hundred pupils split into classes by age. An Infant school and a Senior school with similar numbers of pupils were on adjacent sites and together they provided education for five to fourteen year olds in classes of one age. Sulgrave School was tiny by comparison with two teachers in two rooms teaching all ages. I cannot recall how I or any other evacuees reacted to this situation. I do remember the school bell which hung from the wall about ten feet above the ground and was rung by a wooden pole attached to the bell. I also remember steaming clothes draped over the safety rail around the open fire after pupils had walked into school on a wet day. I remember that Miss Cave wielded a very swishy cane, but I do not recall any of the other blunt instruments she is said to have used. The vicar came in from time to time, maybe weekly, and I still have a copy of his book ‘Fifty Miles Round Sulgrave’ inscribed ‘Second prize for good answering in Sulgrave School Scripture Class’.

school with similar numbers of pupils were on adjacent sites and together they provided education for five to fourteen year olds in classes of one age. Sulgrave School was tiny by comparison with two teachers in two rooms teaching all ages. I cannot recall how I or any other evacuees reacted to this situation. I do remember the school bell which hung from the wall about ten feet above the ground and was rung by a wooden pole attached to the bell. I also remember steaming clothes draped over the safety rail around the open fire after pupils had walked into school on a wet day. I remember that Miss Cave wielded a very swishy cane, but I do not recall any of the other blunt instruments she is said to have used. The vicar came in from time to time, maybe weekly, and I still have a copy of his book ‘Fifty Miles Round Sulgrave’ inscribed ‘Second prize for good answering in Sulgrave School Scripture Class’.

Autumn 1939 was followed by a hard winter and in February heavy snow and freezing rain blocked the road from Stuchbury to Sulgrave with snow drifts and fallen tree branches, preventing us from going to school for about a week. Soon after that we moved from Stuchbury to Spinners Cottages in the village, which eliminated the daily trudge to and from school and brought the luxury of electricity, but water still came from a pump, fifty yards away, and the loo was no improvement.

At Stuchbury we seemed to be exempt from Sunday school, but moving close to the Church meant that, along with my cousins, I had to attend and was also recruited into the Church choir. I remember choir rehearsals with Emma Cave furiously peddling her harmonium! One Sunday we rebelled and slunk off down the lane that runs around the back of Castle Hill, but at the last minute lost our nerve and ran to the vestry arriving just in time to don cassocks and surplices. The choir sang at the wedding of the Vicar’s daughter and although I do not remember anything of the ceremony but I do recall going to the vicarage to receive a half crown which seemed like a lot of money.

At Stuchbury we seemed to be exempt from Sunday school, but moving close to the Church meant that, along with my cousins, I had to attend and was also recruited into the Church choir. I remember choir rehearsals with Emma Cave furiously peddling her harmonium! One Sunday we rebelled and slunk off down the lane that runs around the back of Castle Hill, but at the last minute lost our nerve and ran to the vestry arriving just in time to don cassocks and surplices. The choir sang at the wedding of the Vicar’s daughter and although I do not remember anything of the ceremony but I do recall going to the vicarage to receive a half crown which seemed like a lot of money.

I remember there was some excitement when Bill Wootton in his Hampden bomber flew very low over and around the village.

With the summer came the threat of invasion. I remember Captain Donner, described by my Aunt as ‘Gentry’, spending days on the church tower wearing a steel helmet (a relic from World War1?) and scanning the countryside with his binoculars for German parachutists. Not much chance of that, but I guess he felt he was doing his bit for the war effort. The army set up a searchlight just by the Magpie Road and I remember there was an occasional Church parade for what seemed like a lot of soldiers. Perhaps the numbers were boosted with soldiers from other units.

In the autumn the war became more apparent with Sulgrave and it’s searchlight seeming to be under the flight path of the night bombers flying north. I remember my Aunt waking us one night to see the fire bombing of Coventry reflected in the sky behind the windmill. In those days the windmill was not a residence, but a ruin with the mill stones and machinery in a state of semi collapse within the building. Much of the machinery was made of wood and I remember large wooden gear wheels with individual teeth or cogs set into rim. It was great place to climb and play and probably quite dangerous. I also remember finding a wild bee nest in the hedge by the mill and being shown how to extract small amounts of honey.

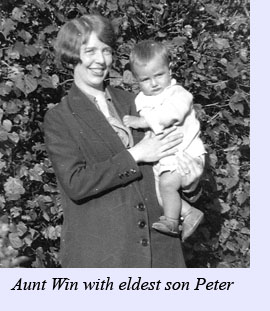

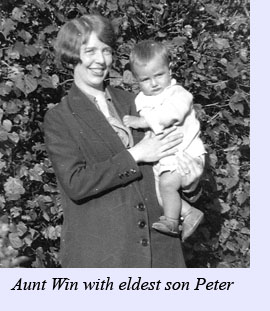

With Autumn came the end of harvest. My Aunt Win kept chickens and we children were recruited/press ganged to accompany her to the stubble fields gleaning for dropped ears of corn for her chickens. One of the chickens was confined to a small coop and fed well to be fattened for Christmas, a primitive form of battery farming. A few weeks earlier we had been out blackberrying so that my aunt could build up a stock of jam for the winter. One of the rewards for picking blackberries was a picnic at the ‘Paddlings’ where a brook ran through a culvert under the railway embankment.

With Autumn came the end of harvest. My Aunt Win kept chickens and we children were recruited/press ganged to accompany her to the stubble fields gleaning for dropped ears of corn for her chickens. One of the chickens was confined to a small coop and fed well to be fattened for Christmas, a primitive form of battery farming. A few weeks earlier we had been out blackberrying so that my aunt could build up a stock of jam for the winter. One of the rewards for picking blackberries was a picnic at the ‘Paddlings’ where a brook ran through a culvert under the railway embankment.

I do not recall that I had any desire to leave this rural life, but having passed the eleven plus, it must have seemed to my parents that I should return home. So one December afternoon in 1941 my Aunt put me on a train at Banbury bound for Paddington. The train was crowded and I sat on my little case in the corridor surrounded by soldiers, many with all their kit and some with rifles. Soon it was dark and there were virtually no lights in the train due to the blackout and I must have been quite relieved to arrive at Paddington where I was met by Mother.

I will always treasure my memories of Stuchbury and Sulgrave and have returned many times although not in recent years.

See here for the memories of other wartime evacuees to the village.

Further wartime memories from the Oral History Project.

TOP

deliveries to listen to the Prime Minister and I well remember the Prime Minister’s solemn tones. But, war or no war, life had to go on and I accompanied my Father when he took his horse drawn milk float back to the depot. Within minutes we saw the barrage balloons beginning to ascend closely followed by the wail of the air raid warning. We continued our journey only to be stopped by a policeman, wearing a steel helmet in place of the traditional headgear, who instructed us to take cover, whereupon my father asked “What about the horse?” Faced with this situation the policeman agreed that we should proceed to the dairy yard as quickly as possible.

deliveries to listen to the Prime Minister and I well remember the Prime Minister’s solemn tones. But, war or no war, life had to go on and I accompanied my Father when he took his horse drawn milk float back to the depot. Within minutes we saw the barrage balloons beginning to ascend closely followed by the wail of the air raid warning. We continued our journey only to be stopped by a policeman, wearing a steel helmet in place of the traditional headgear, who instructed us to take cover, whereupon my father asked “What about the horse?” Faced with this situation the policeman agreed that we should proceed to the dairy yard as quickly as possible. I had come from a Junior Elementary school with several hundred pupils split into classes by age. An Infant school and a Senior

I had come from a Junior Elementary school with several hundred pupils split into classes by age. An Infant school and a Senior school with similar numbers of pupils were on adjacent sites and together they provided education for five to fourteen year olds in classes of one age. Sulgrave School was tiny by comparison with two teachers in two rooms teaching all ages. I cannot recall how I or any other evacuees reacted to this situation. I do remember the school bell which hung from the wall about ten feet above the ground and was rung by a wooden pole attached to the bell. I also remember steaming clothes draped over the safety rail around the open fire after pupils had walked into school on a wet day. I remember that Miss Cave wielded a very swishy cane, but I do not recall any of the other blunt instruments she is said to have used. The vicar came in from time to time, maybe weekly, and I still have a copy of his book ‘Fifty Miles Round Sulgrave’ inscribed ‘Second prize for good answering in Sulgrave School Scripture Class’.

school with similar numbers of pupils were on adjacent sites and together they provided education for five to fourteen year olds in classes of one age. Sulgrave School was tiny by comparison with two teachers in two rooms teaching all ages. I cannot recall how I or any other evacuees reacted to this situation. I do remember the school bell which hung from the wall about ten feet above the ground and was rung by a wooden pole attached to the bell. I also remember steaming clothes draped over the safety rail around the open fire after pupils had walked into school on a wet day. I remember that Miss Cave wielded a very swishy cane, but I do not recall any of the other blunt instruments she is said to have used. The vicar came in from time to time, maybe weekly, and I still have a copy of his book ‘Fifty Miles Round Sulgrave’ inscribed ‘Second prize for good answering in Sulgrave School Scripture Class’. At Stuchbury we seemed to be exempt from Sunday school, but moving close to the Church meant that, along with my cousins, I had to attend and was also recruited into the Church choir. I remember choir rehearsals with Emma Cave furiously peddling her harmonium! One Sunday we rebelled and slunk off down the lane that runs around the back of Castle Hill, but at the last minute lost our nerve and ran to the vestry arriving just in time to don cassocks and surplices. The choir sang at the wedding of the Vicar’s daughter and although I do not remember anything of the ceremony but I do recall going to the vicarage to receive a half crown which seemed like a lot of money.

At Stuchbury we seemed to be exempt from Sunday school, but moving close to the Church meant that, along with my cousins, I had to attend and was also recruited into the Church choir. I remember choir rehearsals with Emma Cave furiously peddling her harmonium! One Sunday we rebelled and slunk off down the lane that runs around the back of Castle Hill, but at the last minute lost our nerve and ran to the vestry arriving just in time to don cassocks and surplices. The choir sang at the wedding of the Vicar’s daughter and although I do not remember anything of the ceremony but I do recall going to the vicarage to receive a half crown which seemed like a lot of money. With Autumn came the end of harvest. My Aunt Win kept chickens and we children were recruited/press ganged to accompany her to the stubble fields gleaning for dropped ears of corn for her chickens. One of the chickens was confined to a small coop and fed well to be fattened for Christmas, a primitive form of battery farming. A few weeks earlier we had been out blackberrying so that my aunt could build up a stock of jam for the winter. One of the rewards for picking blackberries was a picnic at the ‘Paddlings’ where a brook ran through a culvert under the railway embankment.

With Autumn came the end of harvest. My Aunt Win kept chickens and we children were recruited/press ganged to accompany her to the stubble fields gleaning for dropped ears of corn for her chickens. One of the chickens was confined to a small coop and fed well to be fattened for Christmas, a primitive form of battery farming. A few weeks earlier we had been out blackberrying so that my aunt could build up a stock of jam for the winter. One of the rewards for picking blackberries was a picnic at the ‘Paddlings’ where a brook ran through a culvert under the railway embankment.