.

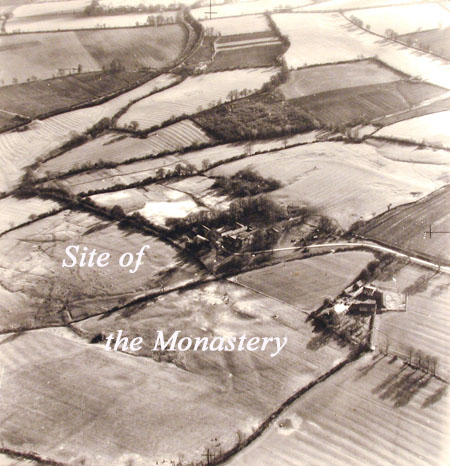

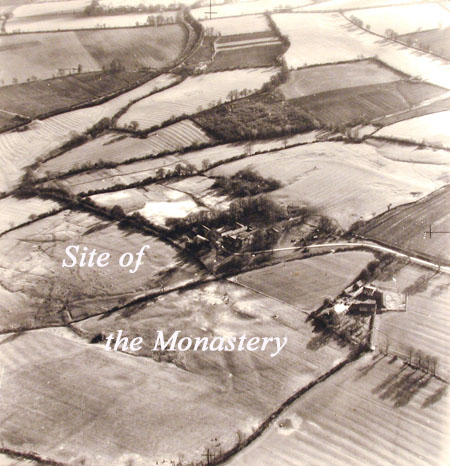

.Aerial view of Stuchbury showing site of medieval village.

THE LOST VILLAGE OF STUCHBURY

(Back to Chapter 1 Index)

ITS SETTING

Stuchbury is a 'lost village' of some 1,023 acres. Bridges, the Northamptonshire historian, describes it as having 'neither church nor town' but says a town did exist at one time but had been destroyed by the Danes. The site of the old village is on the north side of a broad valley cut into upper lias clay, with limestone overlaid with clay on the higher slopes. This geological formation is the cause of the many springs and the areas of marshy ground. It would seem that the original town or 'tun' was of Anglo-Saxon origin, for the boundaries of this village to the present day are for the most part the Saxon double hedge banks.

.

.

Aerial view of Stuchbury showing site of medieval village.

THE SAXON VILLAGE

It was during the late 6th and early 7th centuries that Britain was invaded by the Anglo-Saxons, who, having settled in the south, then pushed their way up into the Midlands. Here, with an altitude of over 400ft, the area was not only remote from the main channel of invasion, but heavily wooded and with a very fertile soil. Here a Saxon chief called Stut is believed to have settled and the name of the place became Stuts Birig or Stuts burh, the defended manor of an Anglo-Saxon. The Anglo-Saxons were good farmers and laid the foundation of our farming practice, with families farming together in settlements and so forming the first villages, or as they were called 'towns'. This was essentially the age of the plough, the land being farmed on the open-field strip system. The open-field often consisted of 'bundles' of these strips which were called furlongs, and the Dairy Ground at the Manor Farm at Stuchbury has a classic example of bundles of strips at right angles to one another showing how much land was reclaimed from woodland in any one year. The entire land of the village was usually divided into two or three big fields and Westfield or Westfyld was a common name which still exists at Stuchbury today. The original village site is the area where Stuchbury Hall now stands, and the sunken roadway that leads from Stuchbury Hall down to the ford would have been the old village street and is a visible feature of a lost village site. The name has changed little over the centuries from being Stutesbirie in the Domesday Survey to Stuchburie in 1621.

ITS FIRST DESTRUCTION

Although Bridges claims it to have been destroyed by the Danes, no great battle was fought in this area, and it is more likely that the cause of destruction is described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 1064. In that year Morcar came south from Northumberland with a request for the King that he should replace Tostig as the Earl of Northumbria. A great many men both Danish and English accompanied him, and they stayed in Northampton while he was gone on his errand to the King in London. Here the Anglo-Saxon chronicle contiues the tale:

'And the northern men did much damage around Northampton while he was gone on their errand in that they killed people and burned houses and corn and took all the cattle they could get at which was many thousands and captured many hundreds of people and took them north with them so that that shire and many neighbouring shires were the worse for it for many years to come'.

This is corroborated in the Northamptonshire Geld Roll for that period by repeated entries of 'waste'. In the Hundred of Cadbaldsstowe in which Stuchbury lay there were twenty six and a half hides of waste, a hide being approximately one hundred and twenty acres.

THE NORMAN CONQUEST

After the destruction of the village Osmond held it freely, and at the Conquest, William the Conqueror was to give Stuchbury along with a large part of the Chipping Warden area to one of his knights, Gilo de Picquiny by name, whose tenants both at Stuchbury and Sulgrave were Hugh and Landric. At the time of the Domesday survey the population had dropped to thirteen and it tells us there was land for five ploughs in the lordship. There were two slaves, five villagers, three small holders and three other men with one plough. There was also a wood three furlongs in length and two furlongs wide, and this is almost certainly a field at Manor Farm called New Piece, because it was the last piece of woodland to be reclaimed. Reginald Isham, who died c. 1960, remembered his father telling him that he recalled it as woodland and this was about the beginning of the twentieth century.

William the Conqueror had given lands in Northamptonshire to his niece Judith and married her to a Saxon called Waltheof, whom Judith was instrumental in getting beheaded at Winchester in 1076. At that time at William's court was a gallant knight called Sir Simon de St Liz. William wanted Judith to marry him, but she refused, so he married her daughter Maud instead, whereon William stripped Judith of all her lands and Waltheof's titles and gave them to Simon de Liz. The land included two hides at Stuchbury, and these two hides he gave to the Cluniac order of monks whose Mother house was the Priory of St Andrew at Northampton.

MONASTIC STUCHBURY

The Cluniacs were alone among monastic orders in establishing cells of four to five and never more than six monks. These would be Italian or French but more usually French. Here at Stuchbury they built a church about the year 1190 dedicated to St. John. The village obviously flourished for by 1377 the Poll Tax reveals that there were 59 taxpayers, which would mean a population of about 250 to 300. Obviously the monks would have needed a considerable amount of labour to build the church, farm the land, dig the fish ponds and carry out other tasks. By 1674 however, according to the hearth tax, there were only four houses left to how did this come about?

As the years went by the monks tended to lose their sense of devotion and from 1300 onwards the strength of the movement began to fail. Richard Layton wrote to Lord Cromwell in 1533:

'At St. Androse in Northampton the house is in dette grethly, the landes sold and morgagede the fermes let owte'.

Other things added to the monks unpopularity, the Hundred Years War with France dragged on, and since dues from the monasteries went to the Mother houses in France it was seen in the light of subsidising the enmy, apart from the fact that average Englishmen disliked the foreign monks. And so the dissolution of the monasteries came about, brought to a head by Henry VIII's divorce from Katherine of Aragon.

.

.

Wool trade

THE WASHINGTONS AND STUCHBURY

Meanwhile in England, London was becoming an important trading centre and with the war with France over, merchants were able to travel abroad. England had long been famous for its wool and cloth, and wool meant sheep. With the dissolution of the monasteries and land being sold cheaply, the well-to-do merchant realised the potential of sheep farming and had the capital to lay down the open fields to pasture, and wool stapling became the trade of the 16th century country gentlemen.

How did this affect Stuchbury? One looks to a north country family, the Washingtons by name, of Warton in Lancashire. Lawrence Washington was bailiff to Lord Parr who was acting as steward of the Kendal estate, and in the course of his duties Washington went to Northampton in 1529 on his patron's business, and there he married a wealthy widow called Elizabeth Gough. He left Lord Parr's household and became at one point Mayor of Northampton. His wife died and he married again, this time to Amy Tomson, widow of John Tomson of Sulgrave, and with this marriage she brought to him the Manors and Rectories of Stuchbury and Sulgrave.

St. Andrew's Priory was dissolved by Henry VIII on March 31st 1537 and the estate was re-granted to Washington and his wife, who had previously rented it, on March 9th 1539 and February 26th 1542. These two grants in respect of Stuchbury and Sulgrave were no more than an acquisition by fee simple of land he had tenanted before the dissolution of the monastery. The Washingtons' cousins, the Spencers of Wormleighton, were amassing a fortune from wool-stapling and Lawrence Washington follwed suit. He went into partnership with his father-in-law, Robert Pargeter of Greatworth, and his wife's brother-in-law William Mole of Stuchbury in 'exploiting the land primarily for sheep' and this led to the demise of Stuchbury as a flourishing village.

ITS SECOND DESTRUCTION

Robert Lawrence's son who had inherited Stuchbury and Sulgrave from his father as well as the advowson of Stuchbury Church collaborated with William Mole's son George and his cousin Robert Pargeter Jnr. in continuing to exploit the land for kine and sheep. It was said they had 'scandalously pulled down not only the parsonage house and all or most part of the said town and parish houses of Stuchbury aforesaid also the parish church itself to make use of the land for wool stapling purposes'. In another account we hear:

'but Stuchbury unluckily possessed no manorial residence, even the parish church and parsonage along with all or most part of the said town had been pulled down by old Robert Washington prior to 1606 to make room for pasturage to the great depopulation of the common wealth and country roundabout'.

So the village population was turned out on the roads and they became vagrants or else went to seek work in the nearest town, for with sheep farming there was little work for them in the village or surrounding countryside. As was said at the time:

'where forty persons had their living, now one man and his dog hath all'.

John Mole lived on at Stuchbury till 1671 and he it was who held court for the hundred of Eadbaldesstowe, later to be incorporated with King's Sutton, in Gallows field on Stuchbury's southern boundary. The gallows themselves, on which cattle theives were hanged, stood by the Welsh Lane which was a drover's road.

.

.

Aerial photograph showing the old main street leading up from

the ford with the site of the main village on the right,

and the medieval fishponds on the left.

THE STUCHBURY FAMILY

What comprised the population of Stuchbury? It was the peasants that were turned out on the roads, but although the Prior of St Andrews was Lord of the Manor, it could be said of the Stuchbury family that they were 'ecclesiastical' neighbours, who were descended from the Saxon cheif Stut, who founded the village. This could mean that they might have lived at Stuchbury Lodge or Stuchbury Hall both overlooking the fields where the church once stood. Records for the Saxon era are rare - but Adam de Stotesbiri is mentiond in 1232 as a clerk and from then on there is an unbroken line of Stuchburys to the present day, many descended from Thomas Stuchbury, the last Stuchbury to own land in the parish, who grazed 1,000 sheep on its pastures. Since he owned his land, why did he choose to leave the village when it was destroyed? Perhaps the Washington/Mole/Pargeter syndicate made him a good offer for his land? The Stuchburys were a family of some substance and moved to Buckingham where they became butchers, brewers and maltsters, and many Stuchburys live in Buckingham to this day. In 1852 William Webster Stuchbury, son of James, who owned a brewery on the site where Paynes' coaches now stand (1992) emigrated with his wife and sons to Australia. There are now 500 Australian Stuchburys - who have published a book entitiled 'Stotesburie - These are our people' and this gives the family trees of all the different branches of the family both English and Australian.

THE LAST TWO CENTURIES

When the church was pulled down some of its stone was used to enlarge the existing farmhouses and on a wall at Stuchbury manor '1736, E.R.' is carved. The late Sir Giles Isham said this would probably be a stonemason by the name of Edmund Reeve who lived at Helmdon and enlarged the house. Interesting pieces of church masonry have been found in the vicinity of all three houses. After the Washingtons and John Mole left, the land was granted out in parcels. With the advent of enclosures the landscape changed again and the thirty-seven acre Dairy Ground at Manor Farm is typical of the large irregular fields of early enclosure. Land changed hands as it has always done over the centuries, landowners and tenant farmers have come and gone. With the advent of the 1939-45 War, the traditional grasslands came under the plough and tractors succeeded the horse, followed in the course of time by ever more sophisticated machinery. Although the pattern of farming practice may have changed, Stuchbury can have changed very little over the centuries, and in 350 years its population has rarely exceeded twenty-five inhabitants.

Leslie Fonge tending his cattle at Stuchbury Manor Farm

STUCHBURY TODAY

Stuchbury Hall, Stuchbury Manor and Stuchbury Lodge still remain of the original village. Stuchbury House, though lived in earlier in this century, is now a ruin. Two cottages stand at Brackley Gate, and the only new buildings have been Spring Farm on the Welsh Lane close to the Helmdon boundary, and a herdsman's bungalow at Stuchbury Manor.

However the sites of the original Saxon village, the medieval fishponds of the Cluniac times and the later village inhabited up to the Tudor period are still very evident. One can stand today in peace and enjoy the tranquil charm of the once, indeed twice, bustling town that was Stuchbury and imagine what a busy community it must have been.